By The Capitol Institute

In Iraqi politics, reinvention is common. Accountability is rare.

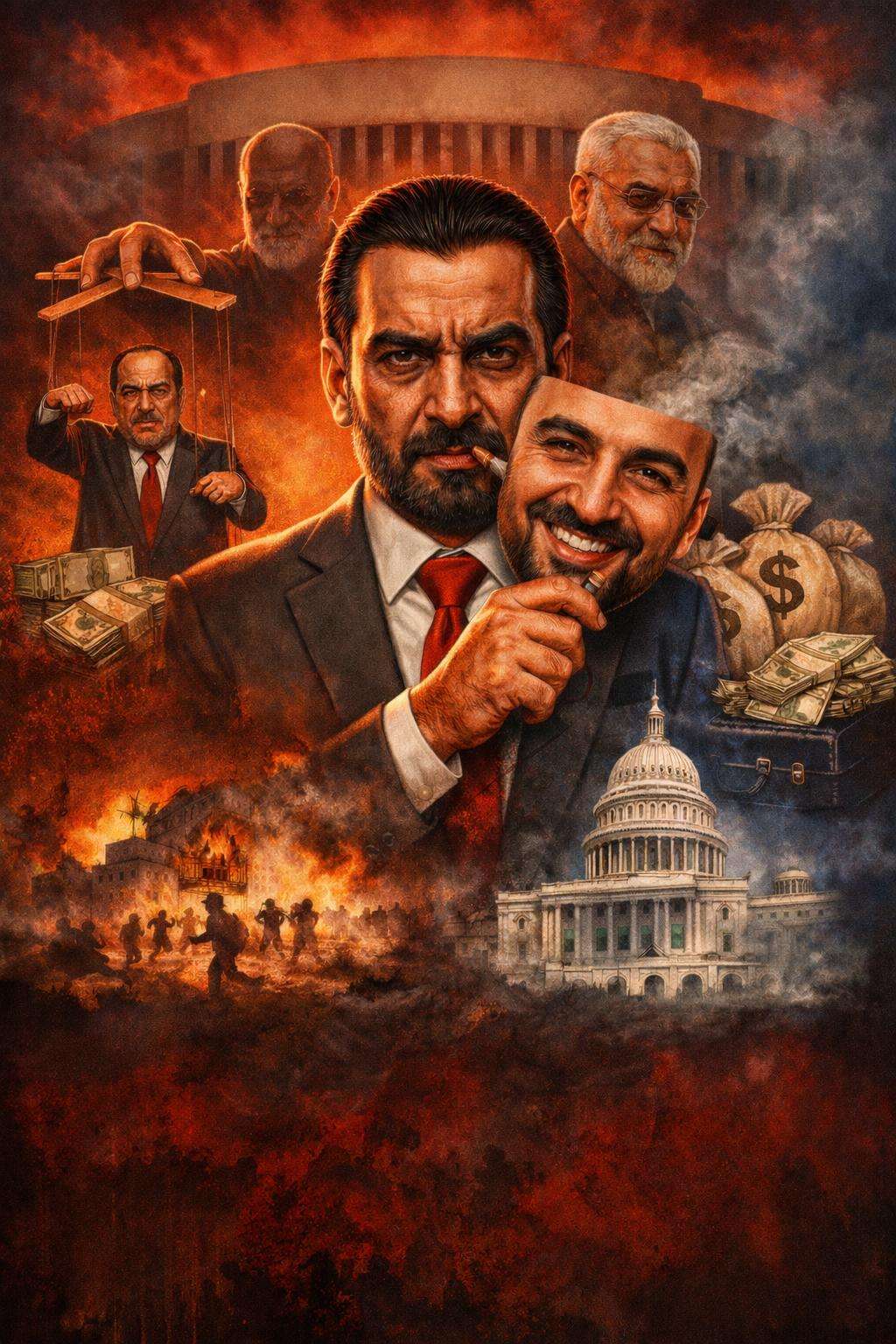

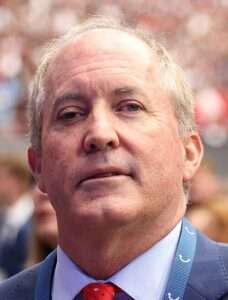

Mohammed al-Halbousi now presents himself as a defender of Iraqi sovereignty, warning against the return of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and citing alleged American objections to his nomination. He frames the debate in terms of economic risk, potential sanctions, and the fragility of Iraq’s relationship with Washington. His message is clear: choosing the wrong leader could isolate Iraq internationally and destabilize the dinar.

Yet this posture raises difficult questions.

Al-Halbousi rose to the speakership of parliament in 2018 during a period when Iranian influence in Baghdad was widely acknowledged as decisive in government formation. At the time, the language of “national sovereignty” was notably muted. Iraq’s post-2003 political architecture — shaped by power-sharing deals, factional bargaining, and external mediation — was not challenged. It was managed.

Today, by invoking U.S. leverage over Iraq’s oil revenues and dollar access through the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, al-Halbousi implicitly acknowledges a structural vulnerability long embedded in Iraq’s financial system. But this dependency did not emerge overnight. It developed during years in which Iraq’s political class — including its parliamentary leadership — failed to diversify the economy, strengthen institutional oversight, or insulate fiscal policy from geopolitical friction.

Moreover, persistent allegations surrounding financial networks, offshore assets, and currency transfer operations — whether proven or not — underscore a broader trust deficit between Iraq’s citizens and their political elites. Reformist rhetoric carries little weight without transparency.

The core issue is not whether al-Maliki should return to office. It is whether Iraq’s leadership class can convincingly distance itself from the very system it helped construct.

Iraq does not need political figures repositioning themselves against yesterday’s allies. It needs structural reform, institutional credibility, and leaders prepared to subject their own records to scrutiny.

Sovereignty is not declared in television interviews. It is demonstrated through accountability.

And Iraq’s public memory is longer than many assume.